The National Association of Artists’ Organizations

by charlotte murphy, naao executive director (1986-1992)

The National Association of Artists' Organizations (NAAO), a Washington, DC non-profit arts service organization, was established in 1982 and lasted about 20 years. NAAO’s first members were the founders and direct descendants of alternative art spaces that formed in the '60s and '70s in direct opposition to the stultifying conservatism of mainstream art institutions. NAAO members were dedicated to creating artist generated systems of support for new work—often commercially unfeasible—that included performance, book, political, sound, mail and installation art, as well as new music and experimental literature. Concretizing the New Left's radical shift to individual freedom that ignited activism in artists, people of color, disabled people, women, and LGBTQ+ communities, artists’ organizations were determined to take action and create change in the art world and beyond.

Some Background According to Martha Wilson (feminist performance artist and founding director of NAAO member Franklin Furnace in New York City), the future of artists’ organizations – bereft of their scrappy pasts of receiving free-to-cheap rents and federal employment cost subsidies through the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, (CETA) – relied on convincing foundation and government funders that the field offered more bang for their buck.

From their start, artists’ organizations enjoyed a supportive relationship with the Visual Arts Program of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). The NEA was founded in 1965 by President Lyndon B. Johnson as part of his Great Society policy initiatives and programs. Brian O’Doherty, the second director of the Visual Arts Program (after Henry Geldzhaler, Metropolitan Museum of Art’s first contemporary art curator), started his seven-year tenure in 1969. He related to Phong Bui in The Brooklyn Rail, “I managed to do a few things for the visual arts, including getting artists to develop their own non-profits so they could get a share of the organizational pie.” Jim Melchert, a Bay Area conceptual artist, followed O’Doherty as director. Before joining staff, Melchert had reviewed artists’ organizations' NEA grant applications as a panelist. He remembered,

“The category was exciting. Artists across the country had decided to take matters into their own hands and create exhibition spaces of their own. The museums had yet to recognize their new modes of art making such as video, performance, sound art, etc. Women and minority groups were also determined to get exposure with galleries of their own. The first audiences for new music were those the alternative spaces made room for.”

The next Visual Arts Program director was Benny Andrews, a New York-based artist, educator, activist, and co-founder of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC). He served from 1982-1984, and joined Melchert in supporting the creation of a new organization devoted to serving spaces. It was the coexisting support within the NEA and the field that brought NAAO forth. Leading up to its establishment, individual NEA field panels voted yearly to support exploratory meetings. Later on, other NEA programs would join to staunchly support the field, most notably the Inter Arts Program and most infamously the Theater Arts Program (think NEA 4).

Searching For Greater Community & Strength On Sunday, June 16, 1982, after a three-day convening, NAAO was voted into existence at Artspaces III at Washington Project for the Arts (WPA) in DC. It was preceded by two independently-organized conferences. The first, in 1978, was the Conference on Alternative Spaces hosted by LAICA (Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art), and was followed by Beyond Survival in 1981, hosted by The Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) of New Orleans. After four years of talking, and as Reaganomics resulted in cuts to the NEA’s budget with future threats looming, agreement emerged that it was time to go national.

NAAO founder Al Nodal (Los Angeles arts administrator, activist, former general manager of the Los Angeles Cultural Affairs Department, and co-founder of the Presencia Cubana Festival in Echo Park) recently wrote in an email,

“When I first got to WPA in 1978 I was searching for a network of peers to work with. DC is the center of associations for everything but I didn't fit anywhere with any museum association. I was happy to get the LAICA invite to this meeting...and it was like heaven. We had an instant national network...then we had a follow up meeting at the CAC in New Orleans and we were a movement. Since we were in DC we felt like the defacto lobbying agency for the movement and were instrumental in creating NAAO.”

Go, Go, Go The steering committee that drafted the plan for NAAO were executive directors Joseph Celli of Real Art Ways (Hartford, Connecticut), Linda Goode Bryant of Just Above Midtown (JAM) (New York City), Al Nodal of WPA, Renny Pritikin of New Langton Arts (San Francisco, California), Robert Smith of LAICA, MK Wegmann of Contemporary Arts Center and Lyn Blumenthal of Video Data Bank (Chicago, Illinois) and Claire Copley, a board member of Artists Space in New York City. In his 2023 book, At Third and Mission: A Life Among Artists, Pritikin wrote,

“During a steamy summer week in DC some two hundred representatives convened to adopt the proposed constitution and found a new organization to advocate for the field and for visual artists nationally. The only serious fissure concerned the proposal of a caucus of attendees who were adamant that the model of the nonprofit status—implying dependency on philanthropy and thus passivity—was not one we wanted to embrace. Chief among them were Joshua Decter of PS1 of New York City, and Linda Goode Bryant from Just Above Midtown.”

Pritikin explains that this can be considered “visionary” of changes to come and the need for independence, but was out of step with the majority of attendees.

NAAO was split into six geographic regions in order to spread out its representation and counterbalance the prevalence of spaces in New York City (which became a region unto itself). From the onset, NAAO’s board represented a combination of large and small organizations spread somewhat evenly across the country. The first NAAO Board included: Helen Brunner of Visual Studies Workshop (Rochester, New York); Jackie Bailey of 1708 East Main (Richmond, Virginia); Sandra Wilcoxon of the Urban Institute for Contemporary Art (Grand Rapids, Michigan); Joseph Sanchez of Movimiento Artístico del Río Salado (M.A.R.S.) (Phoenix, Arizona); Bob Gaylor of Rising Sun Media Arts later named the Center for Contemporary Arts Santa Fe (Santa Fe, New Mexico); Debra Burchett of LAICA; and steering board members Lyn Blumenthal, Al Nodal, M.K. Wegmann, and Renny Pritikin.

Pritikin remembers the emotional intensity after the steering committee’s plan for the new organization was adopted: “It was so moving that our little underfunded movement had emerged united and powerful and national and broadly representative.”

More On Feisty Beginnings A detailed article by Ann Markovich in the New Art Examiner referenced the WPA conference and the previous conferences in LA and New Orleans as consistently contentious debates. Pritikin clarifies some of the angst of the moment:

“The raging debate when NAAO was being considered was whether it was hypocritical for a band of anarchists to join a national, centralized organization. Not only did it strike some as a transgression of our self-image as an alternative network of arts presenters but a threat that we would change and became like…them.” He continues, “We arose in contradiction to the art world’s New York centrism, and the thought of setting up a DC office was hard to swallow. I think a few factors marginalized those opinions. One was the reality that the field was nurtured by the Visual Arts program of the NEA and we had to fight to continue that support. Second was the sheer exuberance of the field, burgeoning with innovation, energy, new artists and the influx of passion from artists who were queer, feminist and of color which overrode any hesitancy. We needed to talk to each other, learn from each other and hang out together every other year at a national conference.”

Definition Blues In a cursory survey of NEA Visual Arts Program funding categories prior to and including 1982, what to call “alternative art spaces” reads like throwing things at a wall and seeing what sticks. There is “alternative spaces,” “artists’ groups,” “artists’ spaces,” “organizations originated by or for artists,” and then, in 1985, after NAAO’s founding, “visual artists organizations.” That sticks, minus the possessive apostrophe. Later the introduction of “artist-centered,” “artist-led,” “artist-driven,” and jokingly, “artist-lite” made their way into the vocabulary.

The Phrase “Artists’ Organizations”

NAAO was never intended to be a machine of standardization or accreditation—that would be anathema. Claire Copley, NAAO's first executive director, explained that the term was chosen for its inclusivity. NAAO founders relied on new members to be “self selecting,” joining because they saw their values and concerns reflected in NAAO’s aims and members. Full voting membership duties included voting for the NAAO board, plus bylaw changes and additions. The criteria stated:

Member Organizations must demonstrate a commitment and responsibility to contemporary artists, ideas and forms, and to equal representation.

Artists must maintain a central policy and decision-making role in Full Member Organizations.

Full Member Organizations guarantee artists full control of the presentation of their work.

Full Member Organizations are committed to paying equitable artists' fees for presenting and exhibiting their work.

Full Member Organizations must be non-profit.

Support/Presentation of an artists work in Full Member Orgamizations has no relationship to restricted membership.

Serving With Others In 1986, I, Charlotte Murphy, became NAAO’s second executive director after Claire Copley–and its sole employee. I executive-directed myself and joined a land awash with executive directors aka DC. I worked with board president Hudson, the founder of Feature. He had an unerring prescient eye for art, an unmatched work ethic, and a great laugh. He was intuitive and empathetic and astonishingly generous with his time and wisdom. He spent three days with me explaining how to run an organization during another hot and humid summer, right before the Hallwalls and CEPA Gallery conference. He taught me how to file and fill out grant forms. No question was dismissed. He never made me feel anything but appreciated. I loved him. As did many others. After his death in 2014, B. Wurtz wrote, “Running Feature more like an alternative space than a commercial gallery was his delight.” Peter Taub, former executive director of NAAO member Randolph Street Gallery in Chicago, Illinois, was interviewed for Hello We Were Talking About Hudson, a collection of interviews and written remembrances collected by Steve Lafreniere. Taub spoke about seeing Hudson at Randolph Street before he worked there:

“The one performance I saw of his there was Sophisticated Boom Boom, which had its own mythology that preceded it. The piece had a kind of grand quality that was built out of very small, ephemeral or vernacular materials.” Taub continues, “He was even head of the board of the National Association of Artists' Organizations for a number of years. That was an amazingly important organization, because for the first time there was a sense of perspective and place in the field. I found it completely unexpected—but I didn’t recognize at the time how brilliant it was—that Hudson maintained his involvement in it while running Feature, a for-profit gallery.”

Other contributors to Lafreniere’s book are Peter Huttinger, Tony Tasset, Kay Rosen, David Sedaris, Gary Indiana, and Hilton Als. Also included is an interview with Hudson by Dike Blair from his book, Again, Selected Interviews and Essays.

Hudson was responsible for hiring Ruby Lerner, who went on to become the founding executive director of Creative Capital, to conduct a field survey of Pennsylvania artists’ organizations resulting in the extensive Organizational Assistance for Artists’ Organizations published in the January-February 1988 NAAO Bulletin.

Following Hudson as board president was Inverna Lockpez of INTAR Gallery in New York City. In 1986 at the NAAO Buffalo conference, she was unanimously elected board president, upon which she immediately resigned, predicating her return on the diversification of the entirely white board. Amazingly, as fortunate as I was to be mentored by Hudson, I was equally fortunate to continue my apprenticeship in artists’ organizations under Lockpez. She was equally way ahead of the curve. She had been active in seminal feminist organizations and theater productions in the '60s and '70s. While at NAAO, she commissioned, published, and widely-distributed through INTAR fellow Cuban American Felix Gonzales Torres’ postcard art, HEALTH CARE IS A RIGHT/ LOS SERVICOS DE SALUD SON UN DERECHO. After, African-American artist Sherman Fleming of DC and Chicano artist David Avalos of San Diego joined the board, NAAO’s commitment to inclusivity never wavered. 1993 MacArthur Fellow Amalia Mesa-Bains wrote that Lockpez, as an artist, activist, strategist, curator, and leader within multiple communities,

“brought her seasoned knowledge and advocacy of diversity to NAAO when it was most needed. Within the larger context of the arts her work at INTAR had been revolutionary, bringing Chicanos to New York City and changing the careers of many of us as well as moving forward the work of women from multicultural backgrounds through a complex lens of feminism.”

The two executive directors following me were people I worked closely with—Helen Brunner and Roberto Bedoya. After maternity leave I resigned to stay home with my daughter Isabelle, and Brunner came aboard as interim executive director. She had worked at WPA as did her husband, Don Russell when I was a wide eyed NAAO volunteer voraciously reading everything I could on the field and blown away by the company I was keeping. Both were graduates of Visual Studies Workshop and both served on the NAAO Board at different times. I spent a lot of time at WPA, and even rented it for my wedding. Brunner and Russell welcomed me into their world brimming with intellect and humor. I learned much from them through hanging out, board meetings, and discussing art and artists’ organizations on a constant loop.

Early in my tenure as executive director, I met Bedoya while touring San Francisco artists’ organizations during a regional conference. He was in charge of the Literature Program at Intersection Arts. We met on the grand staircase of the old funeral home housing Intersection. He was wearing a sweater I still relish. When he came on the board, we were compatriots in laughter and imagining ways to keep widening NAAO’s doorway while staying true to our mission of serving artists and our members. Bedoya became board president after Lockpez. It felt good to have representation at the top from the West to strengthen NAAO and renew its commitment to serving all its regions.

In February 1993, NAAO organized the first and only educational presentation for the National Council for the Arts (NCA), the governing body of the NEA, on artists’ organizations. Strategically organized with help from NEA staff and a few NCA board members, it was held during the ongoing battles over the NEA’s funding of “objectionable” art. It was a celebratory day full of hope for the future and pride in the field for board and staff. 2016 MacArthur Fellow Joyce J. Scott presented her work on slides while detailing how artists’ organizations had supported her work. Bedoya as board president spoke about artists’ organizations that produced publications and identified as community-based:

“In these publications one can read a profile of an arts organization or artist, read essays on aesthetics, view artwork created especially for the publication, read interviews, reviews and news stories on subjects like colonialism, Queer cinema, and where is the intersection between art and citizenship. These publications also provide information on grant deadlines, calls for proposals, and other services available to artists. The distribution of these publications through the bookstores that are a part of many artists' organizations, and through the network of independent booksellers and magazine stores across the country, succeed in getting our thoughts and images to the reading public.” After showing slides of murals created by SPARC (Social and Public Arts Resource Center) throughout Los Angeles, Bedoya explained, “These multi-disciplinary organizations' missions are embedded in a relationship to a community such as in ethnic or rural or inner-city. The link between the health of a community and the production of cultural work informs the practices and aesthetics of these organizations.”

Michael Peranteau, NAAO board member and executive director of DiverseWorks, and also presenting, said,

“There are literally hundreds of artists' organizations throughout the United States. Some present visual arts, some performance, some media, and then some, like DiverseWorks, all of the disciplines. This diverse group of organizations continues to focus on some of the most difficult issues of our time. They are all different but there are several characteristics that we all share, these include:

• Most of us do not have one curatorial point of view, our selection processes for our programs are more open and the input in this process is diverse. You might walk into one of our galleries and see a still life exhibit on one floor and a video installation on another.

• Most of us collaborate with other organizations on a regular basis, this includes not only other arts organizations bur also social service organizations, school districts, parks departments, and many others. This sharing of programs not only increases our audiences but also cuts down on our expenses.

• Each year we must raise our budgets from scratch. We do not have endowments or cash reserves. This means we have no financial safety net if we run into difficulty.

• Our programming includes aesthetic issues of every kind.

• We are community-based which means that each of us is concerned with the specific needs of each of our own communities.

• In many of our organizations, a political and social consciousness is clearly evident and encouraged in our programs. Often we present provocative art where values are challenged and questioned.”

Services to the Field NAAO was a provider of services well-matched to its members. Betti-Sue Hertz, NAAO board member, art curator, historian, and director of Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery, wrote,

“It is no wonder that through the bonds formed across communities of artists that we learned how our local context was a node in a complex web of practices and ideas. In the pre-internet era, NAAO was an engine of connectivity for this growing sector. Looking back we can see the impact of these years—on art making and its reception, especially in the realms of public art, social practice and radical performance art. We became aware of other people’s issues, and the rights that needed defending in different socio-geographical regions—border arts activism, feminist and LGBTQ+ art and politics, racial equity and inclusion, the environment and progressive representational politics—all had a place at the table. We could rely on NAAO to foster dialogue and fight against repressive political policies. That so many members of NAAO are still active in the art field is a testament to the commitment of its members, and its influence on art and culture. It is no wonder that many who were in leadership roles within NAAO, are now at the helm of major arts institutions across the US as well as independent and experimental arts organizations.” Hertz continues, “I would love to see a documentary about NAAO featuring documentation, interviews, retrospection and analysis. It’s an appropriate form to capture its past and communicate its unique place in the history of art.”

Publications NAAO’s most visible services were its publications and conferences. The NAAO Bulletin and Flashes—newsletters and advocacy alerts—were integral to fighting far-right attacks on the NEA, artists, and arts organizations. NAAO published periodic directories of artists’ organizations that included NAAO members and non-members, state and local arts agencies, as well as other art and non-art service organizations. Using the newsletter as our delivery channel, we published papers and essays commissioned and solicited from inside and outside the field. These included Lerner’s previously-mentioned paper, an overview on philanthropy by Pat Anderson, and a collaborative report on art bookstores written by Susan Wheeler, director of Printed Matter and Skuta Helgason, a former director of WPA’s Bookworks.

Rebecca Krafft was our first official editor. She was an artist, musician, and a friend from St. John’s College. Our publications immediately rose in quality. With the board and members substantial help we were able to provide essential reading for the field. Krafft explains in the March 1988 NAAO Bulletin,

“Our initial intent here was to survey through the voices of diverse members of the field the changes that the field has under-gone since the New ArtSpaces Conference at LAICA in 1978 where plans for a national organization were first discussed. To this end, we contacted several people with varying lengths of involvement in the field. Topics were not assigned, rather, the authors were asked to comment on the issues closest to mind. Thus our framework is a rather loose one, and the discussion contained here is by no means complete, nor is it finished. Based on the initial response, we asked Biff Henrich to portray the issues in photographs.”

About two years ago I asked Jeff Hoone, former Executive Director of Light Work of Syracuse about his contribution, Burn-Out and Misconceptions, to which he observed, “… unfortunately I probably could have written it last week.” While some things don’t change, other articles marked the beginning of progress in areas of representation and, in an article by NEA staffer Michael Faubion, blossoming NEA support for the field. Faubion was a Texan who had attended the LBJ School of Public Policy in Austin. He came to government with a commitment to the positive role good governance plays in a healthy society—only to be met by a constant thrum of antagonism under both Republican and Democratic leadership, most devastating was President Clinton’s administration’s decision to cut political liabilities and move support away from individual artists and artists’ organizations (both primary and proud functions of the Visual Arts Program). Visual Arts directors would come and go, but Faubion was there providing continuity, respect, and quiet charm.

Further, the newsletter encapsulated the never-reconciled variance between NAAO members. In one article, NAAO board member Jackie Battenfield (of Brooklyn’s Rotunda Gallery) interviewed Mo Bahc (founder of SEORA Korean American Arts Network and Minor Injury, a NAAO member located in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.) Commenting on the field, Bahc posited that “although they were supposed to be subversive to the cultural system when they first began, they now seem to be more content to act as mediators between the avant-garde and the commercial system.” In contrast, MK Wegmann explicates her consistent vision of the field moving beyond its origins. Wegmann’s view was that “the commitment to an alternative perspective must be carefully examined in its application to responsible institutional growth.” A perfect example of the never-ending debate over the field’s relationship to its roots.

Krafft ended the March 1988 NAAO Bulletin with diplomacy and admiration.

“The issues facing the field are intertwined and complex. None is easily or simply resolved. However, many people are dealing with the same ones and are unaware of their colleagues who are also grappling with them. Knowledge of the commonality of these things gives one strength to persevere, and knowledge of others' experiences imparts a degree of wisdom.”

Other articles included were: Access or No Access: That is the Question by Nilda Perez (founder of the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art (MOCHA); A Special Case: Survival in the Outback by Robert Gaylor (co-director of the Center For Contemporary Arts of Santa Fe); Asian Americans: Defining a Place in Art/History by Margo Machida, (a Japanese-American artist and arts administrator) was a reprint of an article initially published by Henry Street Settlement (a NAAO member); and WARM Gallery: The Fight to Survive by Tamara Blaschko, (the administrative director of WARM Gallery – Women’s Art Registry of Minnesota).

Penny Boyer (NAAO associate director) took charge of our publications soon after the start of the attacks on artists and the NEA. Boyer is a writer, activist and arts administrator now based in San Antonio, Texas. She explains her cultural methodology as “queerating—any kind of off-the-wall-or-on-the-wall, new-concept, culturally encompassing, life-affirming, gender-enriching, pro-active, on-site art project with an element of queer interventionism.” Boyer had the forethought and the energy to create NAAO Archives, a website of substantial amounts of NAAO documents she had saved, digitalized, and shared to counter the absence of a NAAO archive.

As the editor, she, along with staff and board, would gather original documents, announcements, articles, updates on censorship incidents, reports from the field, lobbying information—anything pertinent to our membership and activism. When it came time to publish she would go to work (sometimes all night) with our graphic designer to get it all in. It was her idea to record and transcribe the conversation the board had with Jock Reynolds soon after WPA’s June 1989 decision to take the Robert Mapplethorpe show, The Perfect Moment having been cowardly cancelled by the Corcoran Gallery of Art. It is a close look at a moment when we were figuring out how to fight back, knowing full well that stereotypes of artists would hinder us from being heard. We were wrong. We were heard. NAAO members were responsible for the initial and the strongest push back against anti-NEA mail flooding Congress primarily from one source, the American Family Association, and were key in turning the tide towards majority pro-NEA mailings.

Boyer and Lane Relyea (art critic and writer) co-edited Organizing Artists: A Document and Directory of the National Association of Artists’ Organizations. Made possible by Cynthia Mayeda, Chair of the Dayton Hudson Foundation, this all in one duology of reflection and information includes Vince Leo’s Nobody Remembers Everything, an expansive timetable of key historical dates relating to pro-rights activism, movement organizing, political and art events, and US government actions. It includes events relating to NAAO and NAAO member organizations, and the fast-moving events of the extremely tumultuous culture wars from 1989 to 1990. Leo’s work starts in 1905 with the establishment of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and The Niagara Movement, a committee led by W. E. B. Du Bois that demanded full civil rights for African Americans. It ends in 1990 with a long list of events including: The establishment of the National Campaign for Freedom of Expression, the $68 billion bail-out of the savings and loan industry; the fight by 1708 East Main Gallery, a NAAO member, against a Richmond city order to cover up their window displaying a painting by Carlos Guitierrez-Solana titled IN MEMORIAM; David Wojnarowicz’s suit against the American Family Association for misuse and misrepresentation of his artwork; and NEA Chair John Frohnmeyer’s decision to veto and thereby defund individual artist grants to Karen Finley, John Fleck, Holly Hughes, and Tim Miller for political reasons.

Nobody Remembers Everything: Remembering is Not Enough

When I first read Leo’s chronology, it felt like swimming in my own psyche and discovering events, known and unknown, that created the exact moment of time I occupied. It was revelatory in the ways we construct our morality, our politics, and our sentiments of art and history on a daily basis. Leo remembers,

“When Lane Relyea asked me to create a timetable for the National Association of Artists’ Organizations, I had no idea what that might consist of. That’s exactly why I agreed to accept. By that time, I had constructed multiple timetables and I knew that the joy of making them, like the joy of reading them, lay in the surprise of discovery and the delight of unexpected juxtapositions. Even so I was amazed and humbled by the long history of artists organizing themselves to resist the powers that be, whether that be political, economic, or aesthetic. But the goal of the timetable wasn’t to lionize artists or anyone else; it was to illuminate a landscape of repression and resistance, to give readers an understanding not only of what organizations had accomplished, but also to delineate the massive opposition they encountered at every turn. The NAAO timetable was itself composed in a moment when the forces of repression were in ascendance. Exhibitions shut down. Grants revoked. Organizations shuttered. We heard about it in the news but eventually we came to know it in our bones and in our hearts. Just like we know it today. But as “Nobody Remembers Everything” makes clear: the forces of liberation, justice, and beauty are deeply rooted and constantly evolving. We can be proud of our history and take some degree of solace in that memory. But solace does not mean rest. There is always work to be done and as the final entry of the NAAO timetable declares: ‘Remembering is not enough.’ It wasn’t then and it isn’t now.”

Conferences Michael Peranteau (NAAO board member and executive director of DiverseWorks) wrote in an email that:

"for artist-run organizations outside of the art capitals like New York and Los Angeles, NAAO was a much-needed lifeline and inspirational force. The long-term impact of NAAO cannot be overstated. Its strength was its ability to address relevant topics and connect artists. When the AIDS global epidemic hit in the 1980's many artists’ organizations presented work about AIDS and HIV. Roberto Bedoya and I presented how art and AIDS advocacy overlapped at the NAAO Conference in Minneapolis.”

Conferences, both national and regional, comprise some of NAAO’s most cherished contributions. Each was built upon our core principles of regional, discipline, and organizational size representation and cultural diversity. Though NAAO reflected the underfunded nature of its constituency, it managed—through a combination of collaboration, very low conference fees, low hotel and travel prices, travel subsidies, and a sliding scale membership that included conference discounts—to present a magnetic collection of offerings in the forms of panels, presentations of visual art, new music, and performance art , caucuses, meetings, activities, and parties. People showed up.

An incomplete list of national conferences in collaboration with NAAO and hosted by member organizations includes:

1983: NAME Gallery, ARC Gallery and Artemisia Gallery of Chicago, Illinois

1985: DiverseWorks and Houston Coalition of the Visual Arts of Houston, Texas

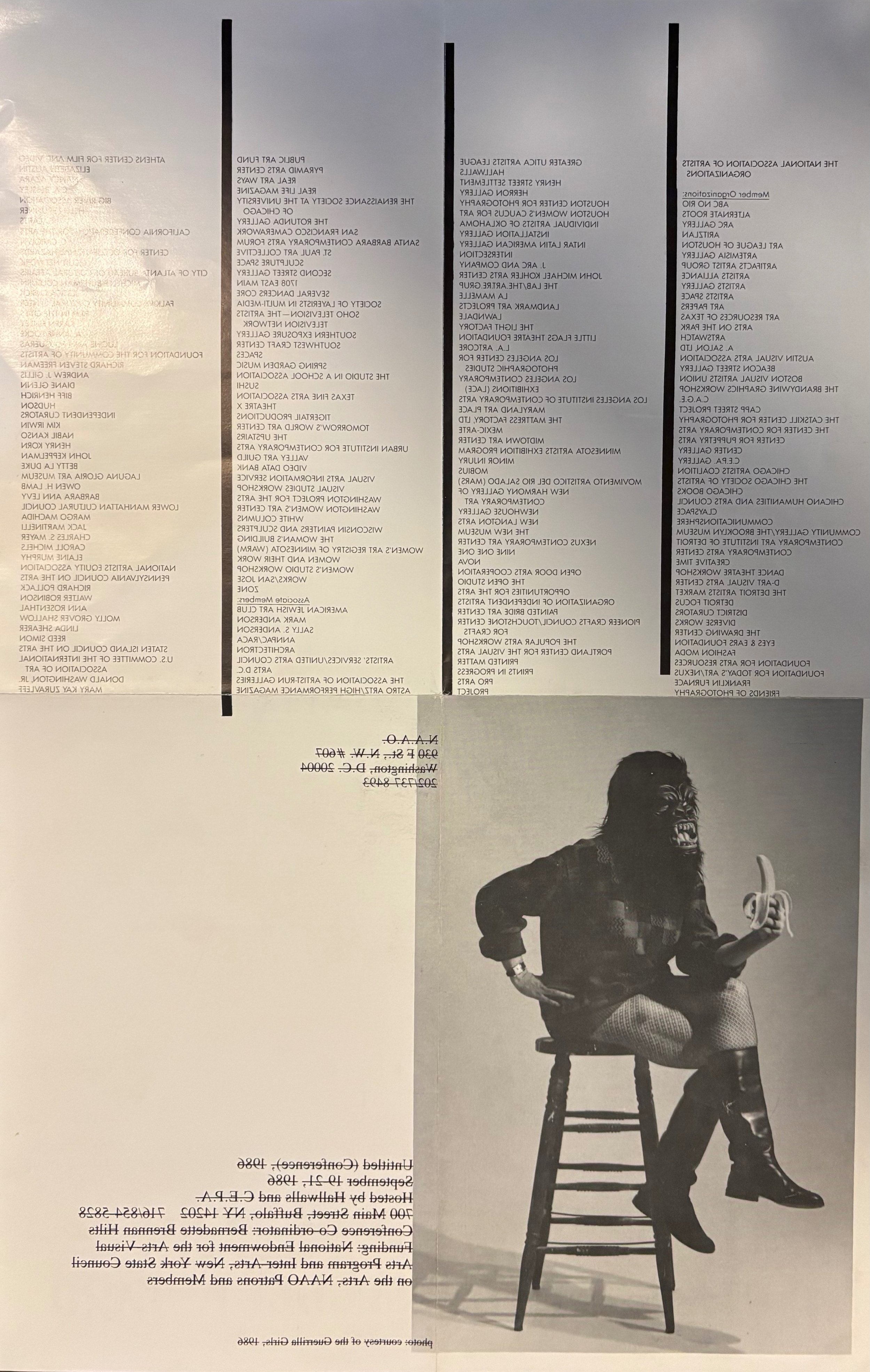

1986: Untitled (Conference), Hallwalls and CEPA of Buffalo, New York

1988: NAAO at LACE, L.A.C.E. of Los Angeles, California

1989: 6th National Conference, Intermedia Arts of Minneapolis, Minnesota

1991: 7th National Conference, Washington Project of the Arts of DC

1992: Mexic-Arte of Austin, Texas 1994: Open Source in Miami, Florida 1995: San Francisco, California 1998: The Courage of Imagination in Chicago, Illinois 2000: New York City

When the Advancement Program (designed to strengthen the administration of small non-profit arts organizations) and Challenge Programs (designed to support exemplary national projects) came back after a brief suspension, itty bitty NAAO opted for Challenge. It was Mary Drayton Hill, NAAO’s fundraiser coordinator, that wrote the grant. No one was allowed to bother her in our close quarters as she meticulously typed the words and collected the materials that got us funded. NAAO’s Challenge grant was for an extensive, multi-site visual arts network that guaranteed artists, fees, and access to new audiences. It was inspired by the National Performance Network, founded in 1985 by David R. White, the executive director of New York City’s Dance Theater Workshop.

Advocacy Inside & Outside NAAO, despite a small staff and budget, was a leading advocate for freedom of expression during the culture wars of the late ‘80s and ‘90s. We rapidly mobilized the membership to respond to attacks against artists, freedom of expression, and government funding for the arts initiated by the religious far-right and strengthened by its Congressional allies. At first the attacks centered on works by Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe but quickly grew to include artists and organizations directly within NAAO’s sphere.

First to be involved was founding member WPA, whose staff, headed by Jock Reynolds, most recently former director of the Yale University Art Gallery, took on exhibiting the Mapplethorpe show The Perfect Moment that DC’s Corcoran Gallery of Art cancelled on June 13, 1989. The Corcoran feared Senator Jesse Helms (R-NC). Helms, a bigot and homophobe, held an inordinate amount of power in the Democratic Senate due to factors including his significant role in getting Republican President Ronald Reagan elected and in convincing other Dixiecrats, far-right segregationist southern Democrats, to follow him to the GOP. Helms brought new money and power to the far-right due to his early adoption and expert-use of direct mail campaigning, partnered with his formidable coalescent abilities; effective manipulation of the media; his willingness to lie about his opponents and most else; and his effective blocking of civil rights, AIDS funding, gay rights, abortion rights, disability rights, religious freedoms, separation of church and state, and environmental legislation. No one denied the harsh realities of Helms’ and the religious far-right’s sudden interest in attacking the NEA but the Corcoran’s preemptive whimpering cave-in was a shock and betrayal felt by many in the arts, the LGBTQ+ communities, the AIDS community, and beyond.

While lobbying Congress and building coalitions with organizations inside and outside the arts, NAAO gained significant press coverage for its unwavering stance in favor of artists and free speech. The board and its members were essential to all NAAO advocacy activities. Lockpez testified before Congress and the NCA in support of freedom of expression and government funding of the arts. Before The Government Activities and Transportation Subcommittee held at the Brooklyn Museum on October 28, 1991, Lockpez said,

“History has taught us that art has always intended to challenge beliefs and conventions, to question unquestionable forms of authority and to manifest the unseen forces of the universe. Since history tends to repeat itself, let's remember an episode in Germany in the mid-twenties. In 1926, the German painter George Grosz and a series of German intellectuals were against a proposal in which the German government was planning to eliminate the ‘filth and obscenity’ that according to them prevailed in the arts of that time. The artists signed a petition against the government and swore to work together against intolerance. George Grosz, the same artist that signed the petition published a portfolio of drawings a couple of years later. Three of the drawings attacked the army, the church and the government. One of the drawings showed Christ on the cross wearing a gas mask and army boots. The title of the drawing was Keep Your Mouth Shut and Do Your Duty. He was put on trial, accused of obscenity and of offending the religious beliefs of many people. This happened 63 years ago….Decency standards are the most slippery of all social covenants. What is indecent today will be household tomorrow. We laugh at the squeamishness of the past. In our time of ultra-rapid change, social conventions and acceptability shift constantly before our very eyes. Only yesterday did the Hayes Office forbid filming a married couple in a double bed. Courbet's nudes, Manet's ‘Olympia,’ were the Mapplethorpe of their day. Now they are calendar art. The body remains a taboo, and contemporary artists have used the body in shocking ways. Artists break taboos.”

While mainstream art service and lobbying organizations of the time did not directly support artists who were coming under attack, and argued that controversial grants were just a few mistakes made, NAAO engaged in a multi faceted and robust campaign to support artists and their freedom of expression. NAAO helped found the National Campaign for Freedom of Expression (NCFE) alongside Joy Silverman, a past NAAO board member and former executive director of LACE. Silverman remembers,

“In 1989, while executive director of LACE, I got a call from Charlotte Murphy at NAAO, our eyes and ears in Washington, DC, that Congress was attacking the NEA for having offended conservatives through its support of the work of artists Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe. Elected officials were actually condemning artists on the floor of Congress!

The art world was very different from today. Art spaces like LACE–also known as artists’ organizations–around the country, were run mostly by artists in tight communication with each other; and they often presented the same work from what was then a smaller pool of artists working in performance art, video, new music, and new dance, expanding their reach and enriching new audiences. From the start we were in this together.

De facto censorship based on gender, class, race, homophobia and more had been in place for decades, but this was new. It wasn’t just about cutting federal funding of the arts; it was censorship out in the open for all to see.”

In late May 1990, NCFE and NAAO attended The Arts Summit, an advisory committee convened by art fan and NEA supporter Representative Pat Williams (D-MT), Chair of the NEA Reauthorization Committee, and the last Democrat from Montana to serve in the House. He was determined to provide Congress and the public with a unified arts stance. This came in the wake of a Republican proposal to restructure the NEA and turn over 60% of its budget to the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies (NASAA) for re-granting purposes—a money grab and laundering scheme at once. Rep. Williams made it clear that the Democratic Congress was behind the NEA as structured. Other groups and individuals invited were the American Arts Alliance (ACA), American Council for the Arts (ACA), NASAA, National Assembly of Local Arts Agencies (NALAA), National Association of Museums, The Association of American Cultures (TAAC), AFL-CIO Professional Employees the Arts, Coalition of the National Writers Organizations, Coalition for Education in the Arts, Creative Coalition, NCFE, National American Design Council, Artists Equity Association, American Council for the Traditional Arts, and two members of the public, and two artists.

The Arts Summit statement Artistic Freedom: Our American Heritage came after four days of semi-seclusion and no press contact. It included support of the individual artist and then it quietly didn’t having been cut from the copies ready for distribution to the press. NCFE and NAAO insisted support for individual artists get put back in, and threatened to boycott the joint statement and release our own. Part of that re-inserted statement said, “All art and work of arts organizations flow from the creativity of the individual artist. We strongly urge the Congress to continue to support this irreplaceable source of inspiration.” NEA Chair Frohnmayer, embattled and wobbling between axing challenging grants and praising them, closely echoed The Arts Summit statement in his Five Point Plan for the NEA that soon followed. Absent was any word about individual artists’ crucial role in art.

At the Edge: The 10th NAAO National Conference was held in October 1995 in San Francisco. Jon Winet, a NAAO board member, served as the conference coordinator. He had experienced first hand the wide range of attacks that the conservative onslaught in DC had on artists and organizations. Winet recalls,

“In 1990, one year or so into my five-year tenure serving as director of Southern Exposure in San Francisco, we were singled out by North Carolina U..S. Senator Jesse Helms as smut peddlers on the federal dime for our exhibition Modern Primitives, curated by the brilliant ReSearch Publications team of Andrea Juno and V. Vale. The show focused on tattooing and scarification. In the year or so that followed the lives of our small part time staff were just about totally upended. Hard times, but greatly made easier with the support of the Bay Area community, from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco to Capp Street Project resulting with the launch of SFBACFE - The San Francisco Bay Area Coalition for Freedom of Expression that included dozens of organizations. At the national level NAAO played an essential role, as did an unsolicited grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. At its peak, weekly SFBACFE meetings had over 50-70 people in attendance. Highlights included participation in the annual Pride Parade and the shrouding of Rodin's The Thinker at the Palace of the Legion of Honor."

Are You Decent? The inclusion of a “decency clause,” a compromise to Helms’ obscenity amendment to NEA legislation, led NAAO to become a co-plaintiff in the NEA v. Finley case, where we joined artists Karen Finley, John Fleck, Holly Hughes, and Tim Miller (known as The NEA 4) in challenging its constitutionality. The decency clause states “artistic excellence and artistic merit” must include consideration of “general standards of decency and respect for the diverse beliefs and values of the American public.” The case was won at every level except the Supreme Court, which, in an 8–1 decision in 1998, ruled against us, upholding the decency clause as it was deemed just another consideration in grant giving and not a specific viewpoint-based restriction. Justice David Souter appointed by Republican President George H. W. Bush cast the sole dissenting vote. His dissent is well written, provides examples of supporting precedent, and finds that the “decency clause” is viewpoint based and thereby restrictive and unconstitutional. His principled opinion was in stark contrast in all ways to the majority opinion written by Justice O’Connor. That was a blurry meandering collection of contradictory reasoning. Lackland H. Bloom, Jr. wrote in his 1999 paper NEA V. Finley: A Decision in Search of A Rationale, “Glaring contradictions in the majority opinion suggest that it was the product of a Court in agreement as to the result but not as to a rationale.”

HIV/AIDS NAAO was woven tightly with individuals and organizations fighting for justice for people with AIDS, as well as advocating for increased research funding and services. ACT UP was a beacon of bravery, and though as a service organization we would never match its level of activism, organizational and individual members did. Our philosophy was to show solidarity with efforts against the far right—a very different stance from the control favored by other arts service and lobbying groups. Led mostly by Democrats, they spent a fair amount of energy on keeping their distance and criticizing artists and their activism, were intent on protecting their pie slice, and flaunted their cynicism over any whiff of idealism, which we connected to rights to be fought for.

ACT UP provided an important perspective on the spineless ways that many in the arts tried to side step or blame artists. Many NAAO members and board members were active in ACT UP. In Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP, New York, 1987 - 1993, NCFE/NAAO attorney Mary Dorman estimated she represented ACT UP for thousands of arrests.” About her activist clients, Dorman told Schulman,

“One thing that distinguished ACT UP from a lot of other activist organizations is not passion, but the depth of the passion, because it was life and death. There was no doubt about it, a lot of demonstrators and activists were going to die, and did die, and knew they were going to die. So arrest was nothing to them, nothing. There was no fear.”

One of the most powerful moments I experienced at the NEA, along with 1993 Nobel Prize Winner Toni Morrison standing up for artists’ organization in her last year on the NCA, and NAAO’s educative presentation, was when ACT UP disrupted an NCA meeting with the chant “We’re here, we’re Queer, get used to it,” protesting the cancellation of grants made to the NEA 4, all of whom were gay rights and AIDS advocates, and three of whom—Fleck, Hughes, and Miller—were gay. There were many in that room, both inside and outside the NEA, who were made to feel exuberant and seen by ACT UP as they chanted while making an orderly exit.

DC was not a progressive place for arts and politics–activism was a dirty word. DC’s arts lobbying cohort inability to acknowledge the connections between attacks on artists, people with AIDS, gay people, and the NEA was infuriating, and as time has shown, extremely short-sighted. Once, an arts lobbyist told me that a lot of young men died in World War II and no one was fussing about that. I still can’t make explicit the confusion or heartlessness or both of that statement, but it was blood boiling for me. And still is. Today we are facing the worst sequel imaginable to those days. Peter Shamshiri, is a lawyer and co-host on two podcasts, If Books Could Kill, and 5-4, a podcast about how awful the Supreme Court is, spoke on the former about how progressives are considered more the problem than the actual enemies of democracy. Mainstream Democrats who he qualifies as having a New York Times (ouch, I am a reader),

“view of the world, which is, yes, reactionaries are extreme in various regards, they're unserious and in fact, they're not to be taken seriously. But the real like problem with American politics is that the left is out of control. And without the left being out of control, the right wouldn't really matter because a moderate consensus would emerge.

It's the left that's preventing the moderate consensus, right? The right is sort of like a clown show off in the distance, even when they are in power.”

On NAAO’s board was Patrick O’Connell, one of the early directors of Hallwalls, and the founding director of VISUAL Aids, a NAAO member and co-habitant of office space with NCFE in New York City. Patrick O’Connell helped start The Ribbon Project in 1991, and in that year’s November NAAO Bulletin—commemorating the second DAY WITHOUT ART, held in conjunction with WORLD AIDS DAY—staff taped a red ribbon to each newsletter, accompanied by the following explanation and instructions:

“Wear a ribbon to show your commitment to the fight against AIDS. The red ribbon demonstrates compassion for people with AIDS and their caretakers; and support for education and research leading to effective treatments, vaccines, or a cure. The proliferation of red ribbons unifies the many voices seeking a meaningful response to the AIDS epidemic.

It is a symbol of hope: the hope that one day soon the AIDS epidemic will be over, that the sick will be healed, that the stress upon our society will be relieved. It serves as a constant reminder of the many people suffering as a result of this disease, and the many people working toward a cure-a day without AIDS. The Ribbon Project is a grassroots effort: make your own ribbons. Cut red ribbon in 6" length, then fold at the top into an inverted ‘y’ shape. Use a safety pin to attach to clothing.”

Patrick’s death on March 23, 2021 broke many hearts.

Advocacy Before Prior to the explosion surrounding Serrano and Mapplethorpe, NAAO’s advocacy efforts were aimed at building ties with other small service organizations in DC, who, unlike our institutional counterparts, did not have regular private access to the NEA Chair–either as a group or individually. We named ourselves The National Advocacy Coalition for the Artist. It was an eclectic group—quite a few of us had one- or no-person offices. Volunteers, usually board members, typically attended in the latter case. The group included, The Association of American Cultures, The National Jazz Service Organization, International Sculpture Center, The Association of African American Museums, and National Artists Equity, a co-founder with NAAO. It was a burgeoning and friendly group that was consciously trying to move forward by respecting our differences and recognizing our commonalities. Like NAAO, a number of them did not survive—each for different reasons—but generally speaking, the days of small-group representation were swept away by the ascension of Americans for the Arts—a “big-box store” takeover that greatly diminished the vitality of arts representation in DC.

We had also been successful getting the term, artists’ organizations into the proposed NEA re-authorization legislation and helped, before the culture war storms, Rep. Pat Williams put together a hearing on the support of new art. Judy Moran, former NAAO board member, testified at that meeting on behalf of the field.

The backlash in the 1990s against individual artists and artists’ organizations resulted in the abolition of most NEA Fellowships and significantly decreased the field’s funding as battles continued over the funding of controversial work and the NEA’s very existence. The argument that the very existence of the NEA was at stake has many permutations over its entire lifespan. During NAAO’s time, it was used as a threat to quiet artists and their supporters while invigorating the mainstream arts troops into a panic of motion and disregard for arguments about freedom of expression and artists’ rights than an accurate reflection of the dangers afoot. Mostly it was never about the existence of the NEA, it was about what kind of NEA would exist. The cuts, the loss of fellowships, and the swallowing whole of the Visual Arts program and others into a restructured NEA was not only a risk-averse, sacrificial lamb decision, but also a case of opportunism by those who saw individual artists and small organizations as a drain on limited funds, and, in my opinion, felt threatened by the rise of both in the years before the rattling events of 1989. The idea that individual support for artists was a step forward in arts funding nurtured and grew under the leadership of Ted Berger of New York Foundation of the Arts, Ella King Torrey, and Anne Focke, an arts consultant who had been the Executive Director of And/Or in Seattle, founder of Arts Wire, and a member of the NAAO steering committee.

Great Things Done Although NEA funding had decreased for the field and NAAO, under the leadership of executive directors Helen Brunner and later Roberto Bedoya, NAAO had strong standing in the arts community and continued to provide ethical and innovative leadership and gained impressive support from new sources. In a letter to the field published in April 1993, Brunner wrote, “We are pleased to include in this Bulletin substantive responses to key issues from three of NAAO's membership caucuses: the working conditions caucus, the Diversity Committee of NAAO's Board of Directors, and the gay and lesbian caucus. In the area of working conditions, you will find an analysis of the surveys distributed at the Austin conference, prepared by Gary O. Larson with an introduction stating NAAO's commitment to work on this issue by board member Joe Matuzak; a paper on board and staff relations by M.K. Wegmann, a founding board member of NAAO [NAAO’s first Board President]; and excerpts from Arts Wire of the ongoing dialogue about working conditions which we hope will give you a sense of Arts Wire’s potential as a communications tool.” Arts Wire was initially led by Focke and Matuzak, a Michigan based poet, and was a program of NYFA. It was an early internet innovation.

According to Wegmann in a phone conversation, the working conditions report made a deep field-wide impression. The NAAO member Alternate Roots, a network of artists and cultural organizers, republished it and distributed it to all its members. The report dove deep into issues that had been discussed before, but never as thoroughly, or through a formal examination of conditions, policies, board, and comspensation and benefits.

Bedoya, recently retired from his position as Oakland’s cultural affairs manager, is widely known and heralded for his decades-long work in creative placemaking and expanding of “who belongs” in the cultural and governmental sectors. One of his NAAO projects, The Co-Generate Project, successfully broke down the barriers that younger people felt in becoming members of NAAO and NAAO member organizations. In an email he wrote:

“Building upon the great work that Charlotte Murphy and Helen Brunner did as EDs of NAAO, I was unsure what would be heading my way as the fourth ED. I was inspired by their leadership which modeled the ways that NAAO empowered talent and communities, listened, and addressed the power of resources and position at play at the national cultural policy table. Yet there was always some sucker-punch ready to be delivered to NAAO’s commitment to beauty and civic life, that one needed to pay attention to in the job.

As the ED when the lawsuit was being argued before the Supreme Court and prior to that moment a NAAO board member/president, my NAAO years shaped my life in so many ways: it deepened my understanding of the power of art; my political education about policy making, and cultural policies; my aesthetic education about new forms of art generated by ‘out of guidelines artists’ characterized by cultural conservative. NAAO’s advocacy labors entailed working with public and private arts funders - those who understood the power of imagination and those who were locked in some old school frame about art purposes. I learned how the entanglement of Culture which is fluid and Policy which aims to fix via rules and regulations, shaped the conditions of art and artists advocacy that NAAO supported . These days in our era of the MAGA Cultural War: our AI-ancestor intelligence of former NAAO staff and board members, needs to be in the mix of resistance to the erasure of art, and artists that enliven our civic imagination. Hopefully, this NAAO oral history project will illuminate how the construction of complicity was never a NAAO homework assignment. That the NAAO community knew deeply how Silence=Death, how it voices shaped the ethics and aesthetics of our democracy, then and now! Onward.”

The Reality Fred Wilson, a NAAO board member and 1999 MacArthur Fellow, said during a 1990 board discussion that it was essential to:

“...plan for the future. Be ready to exist without NEA funds. We need to immediately structure our organization for the time…when we will implement contingency plans to support our organization through a period of no NEA support either our refusal of the NEA to give us our funds. We must consider this the last year of support, dig our trenches and arm ourselves so we can firmly, and without doubts about the future, make decisions on accepting or not accepting funds or fighting for our funds in coming years. NAAO's importance to the field as a whole in regards to the censorship crisis is too critical to not take our lifeblood funds from the NEA at this time. We should not accept the money to merely keep our doors open. We must consider it a time of action/preparation. We must decide what is the final straw, the issue or event”

Things would not work out that way. A combination of economics, exhaustion and bad timing proved responsible. The main strength and the main weakness of NAAO was that it was never about itself. People of great humor were drawn to its sometimes rambunctious, and always deep sense of purpose.

Onwards Always

NAAO ended, but the field certainly didn’t. It still goes strong. It still pushes against the status quo.

Do Look Back At the same time of the early culture wars, museums and other mainstream arts institutions were suffering a crisis of funds and vision. Both Presidents H.W. Bush and Clinton pledged to continue and increase their support from the NEA to aid their renewal. In his 1999 article in Daedalus magazine, From Being about Something to Being for Somebody, the scholar and museum administrator Stephen Weil asserted that for museums to “survive, they had to shift their focus from things to people.” It was artists' organizations that showed them how. Museums found new life by adopting the artists, art, and public engagement and collaborative practices of artists’ organizations, while hiring their leaders, curators, and administrators. The shift made some think that the purpose of artists' organizations was, after many premature calls, officially dead. But that was a misreading of artists’ organizations and their greatest abilities. It’s always been the realm of the possible from which they draw their greatest strength. Riding close with the artist, anticipating needs, and supporting vision has always been done best by the swift-footed.

A number of artists’ organizations have reached or surpassed the 50-year mark, including Franklin Furnace of Brooklyn, Light Work of Syracuse, New York, CAC of New Orleans, Hallwalls of Buffalo, New York, and Alternate Roots to name a few. Victoria Reis, a NAAO staff member with three executive directors, went on to co-found Transformer in DC, a small storefront in Logan Circle that Blake Gopnik called “an art scene in a shoe box” in an essay of the same name. In the field’s tradition of fighting back, Transformer showed David Wojnarowicz’s video, A Fire in My Belly, in 2010 after the Smithsonian’s censorship-driven removal of it from the HIDE/SEEK exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery. In Transformer’s 20th anniversary publication, Reis wrote,

“My early work experience at the National Association of Artists’ Organizations (NAAO) provided me with a life-changing education that contributed significantly to the birth of Transformer. Working out of a two room office at 918 F Street, NW DC I learned about the field of artist-run and artist-centered non-profit organizations…I had the remarkable opportunity to be part of advancing the field of organizations driving new directions in contemporary art.” At the end, Reis writes with characteristic gratitude, “Thank you to everyone who has been part of making a DIY, punk-inspired dream come true…”

What started has not ended. Not at all. People of amazing talent, generous spirit, and deep curiosity will continue to be drawn to this art sector that invites you to come as you are.

Paying It Forward Generosity underlies the reality of artists’ organizations. I don’t mean to imply that it is, or was always, pretty. Not everyone always gets, or got, along. Once it was even suggested that we should clip on yellow smiley buttons to help soften the edges. The fractious beginnings of NAAO—and the ideas and circumstances they represent—ran alongside our development, establishment, and end. This includes the circumstances of fairness and inclusion; of funding competition; the acceptance of government and corporate funds; activism defined solely as against not for the government; spaces as autonomous entities as opposed to becoming art centers of the museum mold; artists and administrators feeling separate from each other; community-based organizations feeling overshadowed by groups that saw artists as their community and vice a versa; career growth frictions (especially for the 2nd and 3rd generation); and the challenge of making a damn living. They are important parts of the whole and, in the interests of growth, learning, and fighting back, we will need to provide them attention and understanding and healing in the years ahead. But they are parts, and in no way do they constitute the majority of moving transforming bits that flow together into a deep river of generosity for artists and for each other.

I was recently in touch with Jeff Hoone, former Executive Director of Light Work and president of the Joy of Giving Something (JGS) foundation. We emailed back and forth about how, despite what looks today like a torrent of money in the arts, the reality has not changed. Very few artists make a living from their art, and fundraising gobbles large swaths of mental and organizational resources.

In Miquel Gutierrez’s 2021 podcast, Are You For Sale?, he describes the uncertainty he experienced during his choreography career, despite having secured important and nationally recognized grants for his work, and having employed nearly 40 people “from project to project.” He invited other artists to share their stories on the podcast. One introduces herself: “Hi, my name is Shannon Stewart. I live in New Orleans, otherwise known as Bulbancha. I’m currently working on an evening- length premiere for an actual presenter, and it is for $1,000 to be spent over three years.” She had yet to have “landed a big one” at the time of the podcast. She ends by listing her side hustles, and shares a common sentiment about how artists would be best helped:

“The side hustles have included being a professional dance party starter at events, polishing wood in a giant mansion for a year, dancing in music videos, being an adjunct professor, cleaning houses and coffee shops, teaching dance to folks with Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, working part of the year in Europe and squirreling away actual artist and teaching fees, using the aforementioned student loan money to get a certification that has paid my bills hand over fist more than my advanced degree. And with the most conflict, I have been an arts administrator, where I can be given a stable ongoing salary, benefits and opportunities for professional growth, failure sometimes, and collaboration, ostensibly in service to artists that get to enjoy none of these benefits themselves. Abolish the foundation, tax shelter, paternalistic, philanthropic, grant maker bullshit, give folks a basic income, healthcare, daycare, eldercare and education, and put a maximum income limit in place, and long live The NAP Ministry.”

Gutierrez comments, “You hear it, right? The frustration, the exhaustion, the anger, the range of jobs that have been part of the financial picture, but also the tenacity, the desire to continue, a drive that's born of both commitment to the work and economic precarity, and the desire to see a different world put into place. It's what dance artists do. Or maybe it's better to say, it's what dance artists are forced to do.”

JGS, the foundation that Hoone helps lead, provides multi-year administrative support to artists. There are not enough of these kinds of grants. Solutions appear before us along the path of the possible and are duly ignored. We admire bursts of artistic energy from the past whether it be the beginning of alternative art spaces or COFO, The Chicano Art Group. The confluence of time, politics, and forms of “free money” (like being a student, living on the cheap, CETA, or rotating on and off unemployment benefits), coupled with funders willing to follow the lead of others, should not constitute a picture of a simpler time. They should provide a map for what fortuitous circumstances of a specific time can teach us about the best practices of giving and receiving. The US has a punishment and a greed problem. We might not be able to shake it, but foundations giving more freely might be a start.

Talking To Ourselves The communities that people build outside of the high-cost, high-maintenance world of the rich are beautiful spaces. Perhaps not always on the surface, but who cares? While tourism and remote working often disregard and exploit the economic realities of people around the world, especially those that live in beautiful places—not to mention the trashing of their quotidian—we should ask ourselves: what are we searching for, and what are we losing?

Money and institutions don’t create art, however you choose to define it. People do. Hustling is a U.S. tradition that we are paying the costs of in ways unimaginable and pervasive to some communities—and all too familiar to others. The lessons my generation were taught—“never again,” “work hard,” “the cream rises to the top,” have proven inadequate again and again. And the lessons we weren’t taught enough—namely to treasure “the small”—are increasingly needed. “The small” is a counterbalance to rampant greed. To counter the boredom of standardization, the sameness of our institutions, the bureaucratization of everything, the gentrification of cities, the abandonment of nature, and the exploitation of the rural we need to support artists and artists’ organizations in a way that asks them only to be themselves.

Gabrielle Hamilton (James Beard Winner in multiple categories and years) closed her lastingly influential restaurant Prune, in face of Pandemic realities. Prune was small and, in essence, artitst-run. Soon after its closing in April 2020, Hamilton recalled in a piece she wrote for New York Times Magazine that she was “driven by the sensory, the human, the poetic and the profane—not by money or a thirst to expand.” Her vision was deeply rooted in the people and places she inhabited:

“I meant to create a restaurant that would serve as delicious and interesting food as the serious restaurants elsewhere in the city but in a setting that would welcome, and not intimidate, my ragtag friends and my neighbors—all the East Village painters and poets, the butches and the queens, the saxophone player on the sixth floor of my tenement building, the performance artists doing their brave naked work up the street at P.S. 122. I wanted a place you could go after work or on your day off if you had only a line cook’s paycheck but also a line cook’s palate…At 53, in spite of having four James Beard Awards on the wall, an Emmy on the shelf from our PBS program and a best-selling book that has been translated into six languages, I found myself flat on my stomach on the kitchen floor in a painter’s paper coverall suit, maneuvering a garden hose rigged up to the faucet. I’d poured bleach and Palmolive and degreaser behind the range and the reach-ins, trying to blast out the deep, dark, unreachable corner of the sauté station where lost egg shells, mussels, green scrubbies, hollow marrow bones, tasting spoons and cake testers, tongs and the occasional sizzle plate all get trapped and forgotten during service.”

We accept change, we move on, and we romanticize the past but that’s because we have to. Why not another way? Why not passion and a paycheck? Hoone writes about his work after retiring from Light Work:

“I’ve been on the board of the Joy of Giving Something (JGS) foundation for the past 25 years and am now the president. We give multi-year general operating support grants to artist spaces all over the country who support emerging and under recognized artists working in photography and related media.

All of these efforts were nurtured by my years of supporting artists at Light Work and through the camaraderie and collaboration with other like-minded artists spaces and organizations like NAAO, NYSCA, and the NEA. So there are models of hope out there and as long as artists have a need to create, exhibit, and share their work with others, there will be people and places to help make that happen.”

Cynthia Mayeda said this in the 2013 GIA Reader Grantmakers in the Arts’ magazine.

“In philanthropy, the power thing has gotten bigger and bigger, and foundations have fallen prey to bureaucratization. This trend may be a function of the increase in the number of claims for funds, but it is regrettable. I think we’ve lost some of the simplicity that is essential to good philanthropy — some of our original astonishment and capacity to be humbled by the work of artists.”

Dreaming Together David Avalos wrote in an email that NAAO offered the chance of, “being in the company of folks who got a kick out of working collectively to oppose institutional and governmental efforts to dehumanize and criminalize our freedom to imagine other ways of knowing and loving each other through the arts, to imagine other forms of beauty as monstrous and marvelous as every-day miracles, to imagine a transformational aesthetics linked with real world political, economic, social, cultural and environmental issues.”

That is so much, and yet all of us wanted more.

Thanks to Ed Cardoni of Hallwalls for images.